Vapor Chamber vs. Heat Pipe: Understanding Their Roles in Thermal Design

Thermal control has become one of the defining challenges in modern electronics. As components operate at higher power levels within smaller enclosures, excess heat can quickly reduce efficiency, shorten component life, and lead to system failure. Data from the U.S. Air Force Avionics Integrity Program shows that heat-related stress is responsible for more than half of electronic equipment failures.

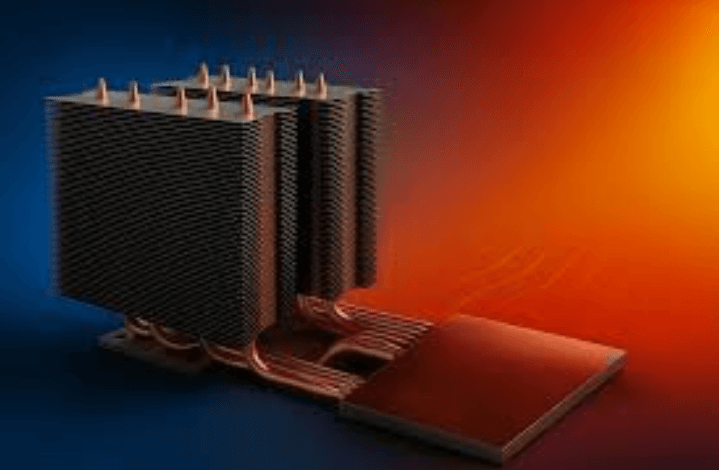

To manage these thermal demands, engineers frequently rely on passive two-phase cooling technologies. Vapor chambers and heat pipes are among the most widely used solutions. Both technologies use a working fluid that changes phase between liquid and vapor to move heat efficiently without external power. Despite this shared principle, vapor chambers and heat pipes are designed to solve different thermal problems.

Vapor chambers are intended to spread heat evenly across flat surfaces, particularly in high-power-density applications. Heat pipes are used to transport heat away from a source to another location, often through confined or complex internal layouts.

Choosing the correct solution depends on heat load, physical constraints, and thermal performance targets.

Vapor Chambers in Thermal Applications

A vapor chamber is a flat heat-spreading device that transfers thermal energy across two dimensions. It is typically manufactured by sealing two thin metal plates, most often copper, to create a vacuum enclosure. Inside the chamber is a capillary wick structure and a measured amount of working fluid.

When heat is applied, the working fluid evaporates at the heat source and spreads throughout the chamber as vapor. As the vapor reaches cooler areas, it condenses and releases heat across the internal surfaces. The wick structure then returns the condensed liquid to the heat source through capillary action, allowing the process to repeat continuously.

This design enables vapor chambers to deliver a highly uniform temperature distribution across large surfaces. They are commonly used in high-performance processors, graphics cards, and compact electronic systems where multiple hotspots must be managed simultaneously. Vapor chambers are well-suited for power densities exceeding 50 watts per square centimeter, helping to minimize temperature gradients and improve system reliability.

The primary limitation of vapor chambers is their planar form, which reduces flexibility in designs that require complex three-dimensional routing.

Heat Pipes in Thermal Applications

A heat pipe is a sealed metal tube, typically made from copper, that contains a wick structure and a carefully controlled amount of working fluid, such as deionized water. The interior of the pipe is evacuated to lower the boiling point of the fluid.

When heat enters one end of the heat pipe, the working fluid evaporates and moves as vapor toward the cooler end. There, the vapor condenses and releases heat into the surrounding structure. The condensed liquid is then returned to the heat source through the wick by capillary action, forming a continuous heat transfer cycle.

Heat pipes are highly efficient and operate without any external energy input. Their cylindrical shape allows them to be bent, flattened, or routed around obstacles, making them ideal for space-constrained designs. Heat pipes are widely used in laptops, servers, automotive electronics, power systems, and aerospace applications. In high-power designs, multiple heat pipes are often used in conjunction to increase the overall heat transport capacity.

Vapor Chamber vs. Heat Pipe Comparison Table

| Factor | Heat Pipe | Vapor Chamber |

| Heat Spreading and Thermal Conductivity | Designed for linear heat transport. Effective thermal conductivity typically ranges from 6,000 to 28,000 W/mK for distances up to 200 mm. Thermal efficiency decreases as length and bending increase. | Designed for two-dimensional heat spreading. Effective thermal conductivity generally ranges from 10,000 to 50,000 W/mK, providing uniform temperature distribution across large flat surfaces. |

| Design Flexibility and Size | Offers high flexibility. Heat pipes can be bent or flattened to fit complex layouts. Common diameters range from 3 mm to 10 mm. Generally lower cost for directional heat transport. | Limited to flat geometries but can be manufactured extremely thin, in some cases down to 0.2 mm. Requires more complex manufacturing and tooling. |

| Heat Carrying Capacity and Isothermality | Typically supports heat loads up to approximately 125 watts per pipe. Provides good temperature consistency along the pipe length but limited surface-level spreading. | Capable of supporting heat loads exceeding 450 watts in electronics cooling applications. Delivers excellent isothermality across the entire surface. |

Cost Considerations

Manufacturing cost is an important consideration when selecting a thermal solution. Heat pipes are generally more cost-effective due to their simpler construction and established high-volume manufacturing processes. Their design allows for efficient production with relatively low unit cost.

Vapor chambers require additional steps, including precision forming of flat plates, high-quality wick structures, internal supports, and controlled sealing processes. These factors increase manufacturing complexity and cost. As a result, vapor chambers are typically chosen for high-performance or space-limited applications where thermal efficiency is a top priority.

Read also: 7 Ways LED Strips Can Transform Your Office Interior

Selecting the Appropriate Cooling Technology

The choice between a vapor chamber and a heat pipe should be based on the specific requirements of the application. Vapor chambers are ideal for systems with high heat density, limited airflow, and a need for uniform temperature distribution across a large surface. They are especially effective when the heat sink area is much larger than the heat source.

Heat pipes are better suited for applications where heat must be transported over distances greater than 40 to 50 millimeters or routed around physical obstacles. For example, an 8 millimeter heat pipe can transport up to 125 watts in a horizontal orientation, although capacity decreases slightly with each bend. In general, vapor chambers excel at spreading heat, while heat pipes provide efficient and flexible heat transport. The optimal solution depends on system layout, thermal budget, and performance goals.